If we are to talk about lockdowns as a discrete event, we need first to focus on the opening months of the pandemic, since this is when the greatest restrictions by far were imposed. In the United States our formal lockdown started March 16th.

This lockdown was not a proactive measure. None of them are. Take the words of Wellcome Trust director Jeremy Farrar: “No one I have ever spoken with is in favor of lockdowns. They are a failure of public policy & ability to use data wisely & act earlier with far less intrusive measures.” Or take the words of infectious disease expert Nahid Bhadelia: “Lockdowns are a reflection of last-ditch efforts required when you let infections run rampant in a community and you have gotten to a point where health systems are overwhelmed.”

We did. By April 11th, 2000 Americans were dying a day (50,000 total by the 24th). We had been letting COVID multiply for weeks without even knowing it, in large part because of a testing shortage. Fauci says on the 12th of March that the testing system is “failing. Let’s admit it.” At that point we had little clue how the virus spread or even where it was. And so, President Trump made his statement on 15 days to slow the spread.

What impact did this have on going out? Mobility data—combining Google’s archive of location histories and GPS data from millions of cell phones—suggests not much. An analysis from June of 2020 immediately looking back shows that mobility decreased massively before the lockdowns even started. There was no sharp decline once they set in, mobility increased throughout the lockdown, and it did not increase sharply once they were lifted. Similar graphs show a sharp mobility decline (albeit less steep) in Stockholm, Sweden right around the same time. Sweden never locked down.

This strongly suggests that the majority of the mobility decrease was voluntary. We can also infer this from the near-universal drop in crime in cities across the United States (shown with careful controls). Crime is of course already illegal so it seems there was an organic incentive to stay inside.

You might then ask why we had to lockdown. There are a few reasons. One is that increasingly tight lockdowns have a diminishing impact on mobility, but an increasingly effective impact on the virus which had only just achieved exponential growth. The second is that COVID is spread asymptomatically, and most economic models assume that the contagious individual does not properly account for this externality (better at self-protection). We ended up going all out since we had no way of knowing what would slow the virus, only that some combination of measures could bring it under control.

Note: Should you doubt this, even studies from December 2020 were saying things like: “it is still largely unknown how effective individual NPIs were. As more data become available, we can move beyond estimating the combined effect of a bundle of NPIs and begin to understand the effects of individual interventions.”

After those first 15 days, states were free to decide their own policy. We know this because some never locked down (e.g. South Dakota) and others overturned their lockdown within weeks (e.g. Wisconsin). States governments trying to contain COVID still had little epidemiological data on which to rely, and they had to be cautious because any policy they might implement would take about two weeks to really set-in. Retrospective data tell us they actually straddled a thin line as the majority of states had a reproductive number for COVID above one at 4 and 8 weeks after relaxation of formal lockdowns.

What followed was caution, but certainly not in the extreme. Epidemiology uses uncertain metrics, and is principally an applied field. Even in retrospect careful analyses fail to explain the majority of case differences between countries. So states re-opened as quickly as they could with what limited evidence they had: “A nationwide patchwork of rules for businesses and residents resulted over months of trial and error, as governors reopened some sectors only to later re-close and reopen them again as infection rates rose and fell.”

And to be clear, reviews in top level scientific journals from which they might have drawn demonstrated that even measures such as school closures did make a difference: “Our findings are consistent with much existing literature—although school closures cannot single-handedly suppress an outbreak, they are generally effective in terms of reducing transmission” (1, 2, 3). You can disagree with these studies, but it’s not like people were just closing things for no reason. It’s certainly not like it was some kind of blind dogma because even deeply conservative states like Texas and Florida found themselves needing to re-implement what restrictions they could in the Summer.

The goal of these measures was never to eliminate the virus altogether. Harvard Epidemiologist Bill Hanage outlines this well. The justification was logistical, as: “arguments about the case fatality rate, the transmission parameters and presymptomatic transmission all miss the point. This virus is capable of shutting down countries. You should not want to be the next after Wuhan, Iran, Italy or Spain” (emphasis mine). He wrote that before New York and other cities were clobbered, proving his point entirely correct.

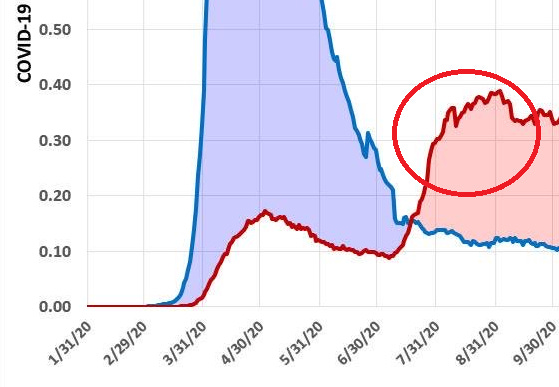

The ensuing lockdown brought things under control to then allow states to choose and pursue a protective policy. Robust data (1, 2) show that COVID declined in most places to below R=1, which as with any wave’s decline is a combination of infection and mobility reduction. We know it wasn’t all infection because the overall wave in the US didn’t dip completely and was able to resume its growth in the summer post-NPIs. The importance of behavior was predicted in advance: “the U.S. may sustain a constant first wave that just continues to crest. The political willpower necessary to limit transmission…seems, unfortunately, to have been snuffed out.”

This unwillingness to self-restrict led to another wave, which we know was behavioral and not seasonal because COVID is a winter virus. Scott Gottlieb describes it well: “In July and August, when a heat wave struck the Sunbelt and people were driven inside for air-conditioning, the crowding fueled a dense epidemic. However, at that point, people in states like Arizona, Florida, and Texas were psychologically done with lockdowns…People started to go out again, creating informal new norms, and governors sought policies to conform safely to what people were already doing.”

They were ultimately unable to keep things safe. This was the consequence:

Undoubtedly, there are other factors which predict a wave. But throughout the first year—during which lockdowns and NPIs were most politically salient—most epidemiologists argue that human behavior was important. Coronaviruses are better at circulating persistently than something like pandemic flu, whose waves actually did come and go fairly completely.

COVID on the other hand didn’t really have discrete waves: “The U.S. as a whole [saw] regional curves go up, dip, climb even higher, dip a bit less, and then ascend still higher to set new records nearly every day and every week.” This meant that it was always capable of mounting with no way of knowing for sure where because: “There is no consensus on the origin of this [wavelike] pattern.” For COVID that seems less applicable because it was always lurking at relatively high concentrations (the mystery with flu is how it goes from 0 to 100). And when we look back, behavior is an obvious driver in nearly every wave.

It seems clear that willingness to change behavior is a product not only of basic human interests, but also ideas and experience. Epidemiologists have found that areas which had COVID worse early on showed significantly more residual control over the pandemic going forward. States that are socially linked both saw decreased mobility if one locked down. We know that watching specific news programs correlated with non-adherence to NPIs in Spring 2020. We know that trust in government was significantly correlated with overall case rates. And we know that those who overestimate COVID’s transmissibility were less likely to adhere to NPIs.

If these measures worked, and indeed everything thus far suggests they kept the virus in check, then we must acknowledge that people made conscious decisions which increased or lowered their risk. This wasn’t possible during the initial wave in dense, blue cities when we didn’t even know how COVID spread and how fast it was about to hit us. Afterwards it empirically was.

And to that point, the winter wave seemed largely driven by human behavior. We see an all-time high in air travel prior to Thanksgiving, which is followed exactly two weeks later by 200,000 cases a day. The record is broken again leading up to Christmas, and two weeks later we have 313,000 cases a day and 8,345 deaths in 48 hours. Of course, people holding in-person holiday gatherings was not an inevitability. Christmas and Thanksgiving do not provide some unique mood boost that could not be obtained by socializing safely. They are cultural events some people partook in and others did not. And for those who did, it was a human choice that obviously spiked COVID.

Many political figures and even some doctors enabled them by writing things like: “Americans are saying that despite all the damage done by COVID-19, despite the rising cases and at-capacity ICUs around the country, their desire for human connection is so great, that they are willing to take the risk and have Thanksgiving. Americans are, in effect, expressing the longing and desperation of their soul.”

There’s value in eschewing abstinence. But this statement is an absurd hyperbole which naturalizes poor reasoning. Many people were able to forego normal festivities under the premise that an extremely effective vaccine was right around the corner. Their willingness to do so at the height of the pandemic undoubtedly saved many lives. It was a testament to the fact that human behavior is influenced by rhetoric, and has life or death consequences. Public health commentators who treated our sweeping differences in this respect as a given instead of explaining risk fooled people.

It also seems clear that the pre-existing surge in red states provided fuel for the much worse winter wave as well. There can be no doubt that intermixing between red and blue winter travelers infected the latter. Sequential spread between communities suggests virus in one place spread to the next. The pre-existing summer wave absolutely erupted during the winter. All of this affirms the general approach of keeping the virus as contained as possible to limit both future and splash damage.

After the winter wave, vaccination would become the most important factor in controlling transmission and deaths by far (boosting would prove similarly important during Omicron). This of course is not relevant to the current discussion. And unlike most I am committed to maintaining some sort of formal definition of lockdowns, which simply did not happen in 2021.